|

| You vill take ze mathematics and you vill like eet. |

So I set myself out to learn to love math. Nobody liked their first sip of coffee nor their first cigarette nor their first alcoholic beverage, but people are addicted to these things for a reason: they're great. I postulated that perhaps my relationship with mathematics would be the same way, that perhaps mathematics (and maybe everything) was an acquired taste. All I needed to do was immerse myself in it, force myself to face it and take a cheerful attitude about it. I needed to want to love it as well as expose myself to it.

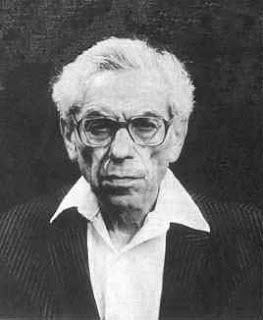

The Man Who Loved Only Numbers is a book about Paul Erdős, a 20th century Hungarian mathematician who was extremely prolific in his publishing and extremely eccentric in his habits. The aggressive, intellectual rat-race view of mathematicians you get from movies such as A Beautiful Mind and Good Will Hunting wasn't something I could fall in love with, but this Erdős fellow was poor, weird, and happy. He really loved math, and it allowed him to live in his own little world where he didn't need the things that other people need. He is now extremely famous among mathematicians, but fame never seemed to be his goal as much as the joy of solving problems. I feel moved by a witness so fervent in his faith.

This book not only gives the story of Erdős, but also some of the story about mathematics. From Pythagoras to Euclid to Newton to Riemann to Gödel, the evolution of mathematics and mathematical proofing takes the weirdest and most intriguing turns. So many who like mathematics use the word certainty to describe the field, but it seems to me that, again and again, so much of what we thought we knew in this perfect undertaking turns out to be an oversimplification of the case. The words "non-Euclidean geometry" are exceptional for carrying the properties of being both bizarre and cliche. And the idea that so many of the problems are the most difficult yet the most accessible - Fermat's Last Theorem, for instance, a simple conjecture which stood for 350 years before being proved - makes an interest in mathematics one which is immediately accessible.

If I'm to go to graduate school in economics, an intensive education in mathematics is going to be required. If I am to be good at my craft, which I aim to be, I must have a passion for all types of math. It will take immense sums of time and effort, and will require changes fundamental to my personality and lifestyle.

But I think it can be done.

No comments:

Post a Comment