|

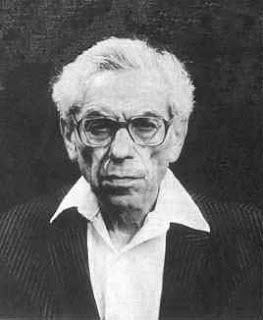

| Mittens is above all this poor-people talk. |

The reason centers around the fact that most of his income (along with Warren Buffet, who has been patently misleading the public on the topic) is derived from capital gains and dividends, which are taxed at the corporate level before being passed through to the individual. In essence, it is a type of double taxation which occurs pretty directly - your money doesn't just get taxed when you get it, but it gets taxed while the check is still in the mail as well. This makes his actual tax rate much higher.

The more orthodox case of double taxation also applies to Mitt, and it's even more important. Imagine you are a doctor who has an extra $10k to spend after a year of budgeting. You have narrowed down your purchase decision to two options: a pair of new jet-skis, or an investment in a local restaurant. From the jet-skis you get a return of glorious fun with perhaps a special someone, and from the restaurant investment you get a return of equity and the capital gains that come from dividend payouts.

Obviously, the returns from the jet-ski option are not taxed by the government besides sales tax and licensing (you can't tax fun!), but the returns from investing in the restaurant - the option that provides a real return to the community - well, those are subject to an unhealthy dose of both corporate and personal taxes. This means that our tax code is biased against productive spending, and for that reason we try to keep the percentage rate as low as we can (hence lower tax rates on dividends and capital gains).

Mitt Romney has made piles of money, so I understand some of the punches thrown over his tax rate. Spraying venom at a policy that keeps money employed in useful ventures instead of extravagant luxuries, however, is not a reasonable attack. Let's hope people remember that after the political dust has settled.